In fiction, we like our heroes and villains clearly labeled. Heroes save the day. Villains cause the problems. Heroes protect the innocent. Villains threaten them. It's clean, comfortable, and absolutely nothing like real life.

My father was both my hero and my villain, sometimes in the same day. He was the man who jumped into an icy creek to save me when I fell through the ice, spending the entire walk home telling terrible jokes to keep my spirits up. He was also the man who, in a manic rage, raised a baseball bat toward my mother while we children watched in terror.

How do you write that person? How do you capture someone who was simultaneously the best and worst thing that happened to your childhood?

The Same Hands

The hands that taught me to tie on fishing lures – patient, steady, guiding my small fingers through the delicate work – were the same hands that threw a chair through a bank window.

The voice that read me bedtime stories, doing all the character voices until I giggled myself to sleep, was the same voice that screamed paranoid accusations at 3 AM.

The man who spent seventeen hours straight building us an elaborate storage box for the town pond – complete with shelves and drawers, chained to a tree so we kids could bike there and fish anytime without hauling our gear – was the same man who spent seventeen hours convinced the government was monitoring him through the microwave.

When I write about these hands, this voice, this man, which version am I supposed to choose? The answer, maddeningly, is both. All of it. The full catastrophe of his humanity.

The Bipolar Excuse That Isn't an Excuse

Here's what makes it even more complicated: My father had bipolar disorder. There's a medical explanation for the transformation from hero to villain. His brain chemistry would shift, and suddenly the father who was teaching us to ride horses would become a stranger who thought he was receiving divine messages through the radio static.

It would be so easy to write: "It wasn't him, it was the illness."

But that's too simple, and also not entirely true.

The illness influenced his actions, but he still made choices. He chose to stop taking his medication because he liked how mania felt. He chose to lock us in Mom's store during a paranoid episode, convinced people were trying to kill him. He chose to pursue his delusions even when part of him knew they were delusions.

But he also chose to seek treatment, eventually. He chose to keep fighting for stability. He chose to love us as best he could with a brain that kept betraying him.

How do you write about someone's choices when their ability to choose was compromised but not absent? How do you assign responsibility without assigning blame? How do you show understanding without excusing harm?

The Trauma of Love

The hardest part about writing my father as both hero and villain is admitting that I loved both versions.

I loved the manic dad who bought a chariot for twenty dollars and took us on ridiculous adventures through downtown. That dad was exciting, unpredictable, electric with possibility.

I loved the stable dad who taught me to fish, who worked hard at his landscaping business, who showed up to every wrestling match.

I even loved – and this is the hardest to admit – something about the chaos. It made us special. We weren't boring. We had stories. We had adventures. We were the family with the chariot, the family who transported horses on a flatbed trailer, the family where anything could happen.

But "anything could happen" included violence. It included fear. It included my ten-year-old sister throwing herself on top of my mother to protect her from our father's rage.

How do you write: "I loved the thing that hurt us"? How do you admit that trauma can be addictive, that chaos can feel like home, that you can miss the very thing that damaged you?

The Death Complication

When I started writing my memoir, Dad was still alive. The challenge then was writing truthfully while knowing he might read it, might be hurt by it, might have his own version of events that contradicted mine.

Now he's gone, and the challenge has shifted. Death has a way of sanding down the rough edges of memory. The villain parts start to fade while the hero parts glow brighter. It would be so easy to write him softer now, to let grief edit out the worst parts.

But that would be another kind of betrayal – not of him, but of the child I was, the children my siblings were, the woman my mother was. We lived through the villain parts. We earned the right to have them acknowledged.

Yet I also feel the pull to protect his memory, to honor the man who, despite his illness, tried to give us adventures and experiences beyond our small-town Kansas life. He failed in spectacular ways, but my God, he tried.

The Both/And Solution

I've learned that the secret to writing someone as both hero and villain is to refuse to choose. You write the both/and:

He was a good father AND a dangerous one.

He loved us deeply AND he hurt us terribly.

He was mentally ill AND he was responsible for his actions.

We were traumatized AND we were loved.

We survived despite him AND because of him.

Every sentence about him could end with "and also the opposite is true." That's not bad writing – that's accurate writing when you're describing someone whose brain contained multitudes, not all of them safe.

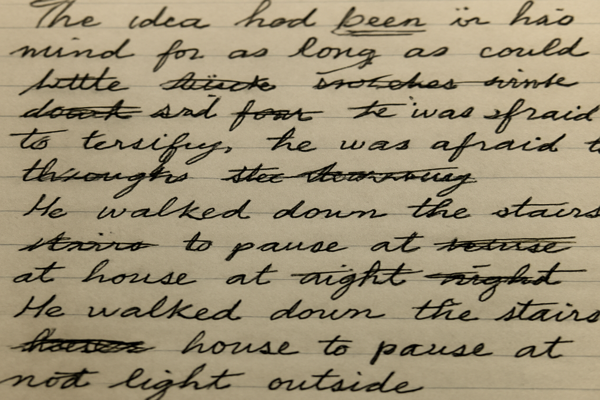

The Paragraph I Keep Rewriting

There's a paragraph in my memoir I've rewritten dozens of times. It describes a moment when Dad was teaching me to ride a bike. He's running beside me, one hand on the seat, encouraging me. "You've got it! You're doing it!" His voice is proud, excited, fully present.

In one version, I write it as pure hero – the devoted father, the perfect teaching moment, the kind of memory that makes you ache for childhood.

In another version, I include what happened an hour later – how he suddenly became convinced the neighbors were spying on us, how he made us go inside and hide, how the beautiful morning turned dark and frightening.

The version I finally kept includes both: the golden moment and its shadow, the hero and the villain, the father who lifted me up and the one who taught me to be afraid. Because that's the truth – not one or the other, but both, always both, forever both.

"Some people are algebra problems with clear solutions. My father was more like quantum physics – existing in multiple states simultaneously, impossible to pin down, following rules that seem to contradict each other but somehow coexist."

What This Means for Other Writers

If you're writing about someone who was both hero and villain in your life – a parent, a spouse, a friend – here's what I've learned:

Don't choose sides. Let them be both. Let the reader sit with the discomfort of that duality.

Show specific moments rather than making general statements. Instead of "he was sometimes cruel," show the specific cruelty. Instead of "he could be wonderful," show the specific wonder.

Acknowledge your own complicity and confusion. We aren't neutral observers of our heroes and villains. We're shaped by them, sometimes in ways that make us unreliable narrators of our own stories.

Let yourself feel both grief and anger, love and resentment. They can coexist on the page just like they coexist in your heart.

Remember that truth is more important than consistency. Humans are inconsistent. Capturing that inconsistency is more truthful than forcing them into a single narrative box.

The Final Truth

My father was not a hero who sometimes did villainous things. He was not a villain who sometimes did heroic things. He was both, fully and simultaneously, until the day he died.

Writing him as both hasn't resolved anything. It hasn't led to forgiveness or understanding or peace. What it has done is allow me to stop trying to solve the equation of him. He doesn't add up neatly. He never will.

Some people are algebra problems with clear solutions. My father was more like quantum physics – existing in multiple states simultaneously, impossible to pin down, following rules that seem to contradict each other but somehow coexist.

The challenge isn't to make sense of that. The challenge is to capture it, to show it, to let it exist on the page in all its messy, painful, beautiful contradiction.

Because that's what he was: a contradiction we called Dad. A hero who hurt us. A villain who loved us. A man whose brain made him both our greatest adventure and our deepest trauma.

Both/and. All of it. Forever.